Working styles and methods (I). Digital Manufacturing and Prototyping

This one-year trip to something quite new was very interesting for me. I learnt many things, but what was probably more interesting was the “discovery process“. What my expectations were, what and how I learnt and what are the opportunities I see.

Expectations and doubts

I was expecting some engineering. To me, it means learning a process, using tables, books, and fix parameters for each of the works, always obtaining the same results, accurate and reliable. This is something that is not happening at all. In the beginning, I thought, “It’s my problem, I don’t know enough”, but it was only partially true.

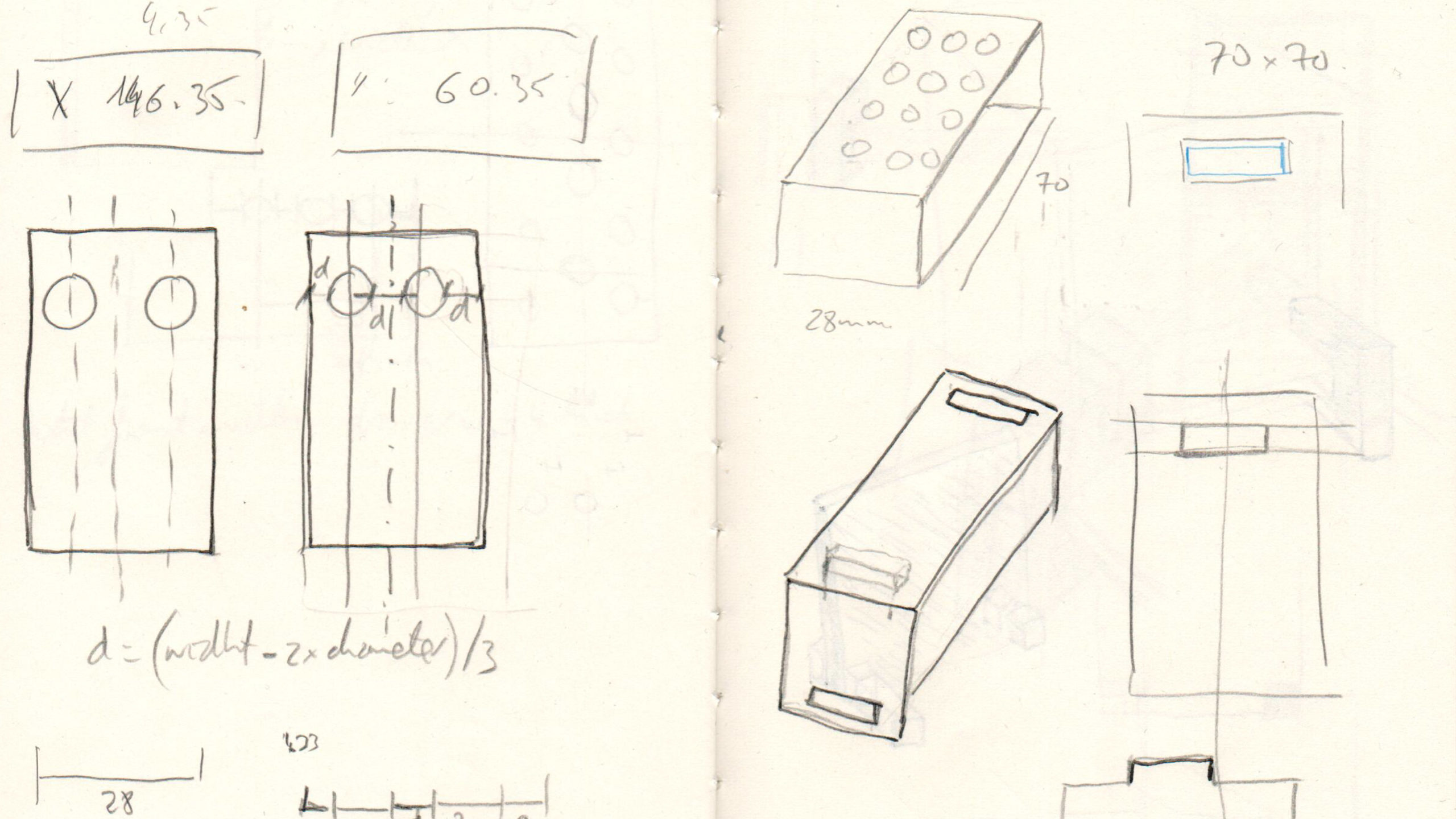

Of course, the more I know, the better results I have, and everything turns out to be easier. But there are always small variations and adjustments, and maybe this is the hardest lesson I learnt. The second lesson was: the first time you produce something, it is not a product it’s just a prototype, and so the second and third ones may be too. I was hoping to have a ready product for the first time because I’m doing smalls products for myself more than prototyping.

And that’s not wrong, that’s the concept of prototyping. It doesn’t matter how many times I review the design, the first time making the product, I always find mistakes and some improvements to make. That’s exactly what we are looking for using these machines and processes: to create several prototypes before manufacturing.

For creating only one product, the time and the cost of the wasted materials make no sense. Well, you could do very customized products and sometimes that makes sense to the investment. Anyway, having a specific product to create is the perfect motivation for learning. Without this goal in mind, it’s complicated for me to learn. Everything is right, everything works and everything is forgotten very fast.

Knowledge and experience.

When I didn’t have the information that I needed, I asked questions to the people around me. Usually, the answer is “there is a lot of knowledge in the community”, and that’s true and nice. It’s one of the advantages of being in a coworking. But that’s not always perfect. I always answer: “Yes, but at the beginning of the times there was knowledge in the tribe, and later we invented the books, and later on we founded the Universities”. Well, I’m still looking for the truth.

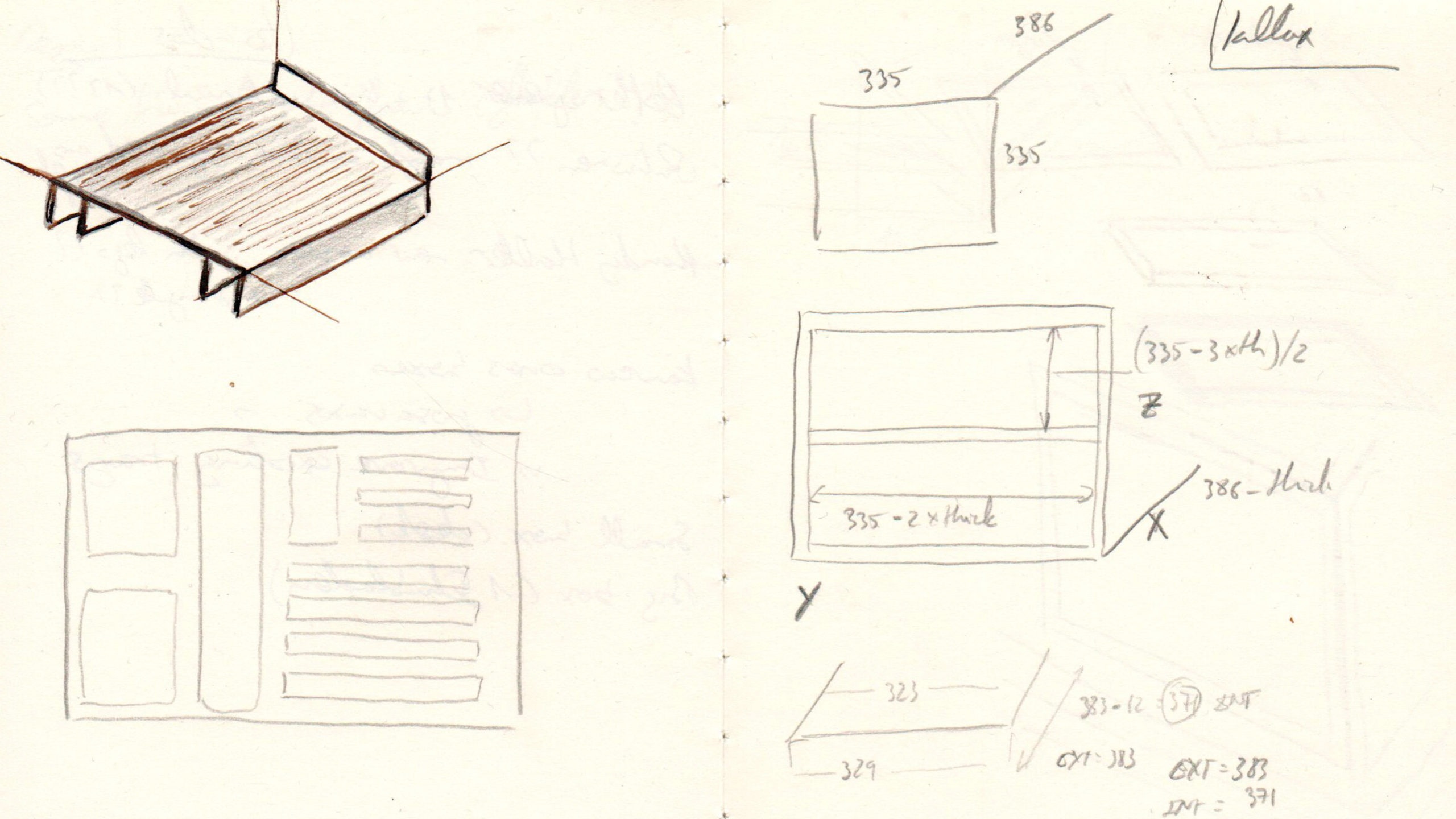

What I’m really missing are procedures in design, but mainly using the machines. With some experience, not so much, they are not highly complicated, but the first time in front of them, it’s chaotic. In the end, there are many software, file formats and parameters, and a list could help. I’m now working on a small user’s guide for 3d-printing and laser cutting. Till now, I only have a checklist in my notebook.

These documents with procedures are also handy when it’s a long time that you didn’t use a machine. There are many settings that you only need the first time you use a program or machine, and then they are fixed forever. For this reason, people with experience forget these steps, which are critical for beginners, and they don’t reflect them in documents or courses. These are the important things at the beginning that we forget very fast in daily practice.

From tribe knowledge to absolute truth and science, it should be a middle point. I think a good solution is to have: checklists, tables with parameters and documented examples and specific cases.

I have the feeling that every new person in Motionlab faces the same problems and we all waste time because of it. It’s true, also, that this time is part of the learning process.

Engineers and makers.

I found two different profiles: more engineers and more makers. As mentioned, I’m in the first group. I would like to understand everything to make the first perfect design model and achieve a perfect product. Now I know that it’s probably not possible because I’ll find some mistakes and many improvements in the first model.

I need a long process to have something ready: check everything two times, draw schemes, measure everything… and at the end, there are always mistakes. For example, with moving pieces. I don’t do a simulation on the computer (next thing to learn in Fusion 360), and I always have surprises, sometimes embarrassing ones.

Makers (or sloppy makers, for me) have a different approach. They do the first design, they find mistakes in the first prototype, they make corrections, and they repeat the process one, two times or more until they have something right. It sounds faster, but in the end, I think the time from the beginning to the ned is similar, and here less learning and knowledge is generated.

Both systems have pros and cons, and the decision is coming to the mindset of each one, and also from how you feel wasting some material, that is a pity for me. As an amateur, it’s not nice, but from a business perspective, time is more important than 20€ of material.

There are also two profiles: discoverers and doers. I’m in the “explorers” group: we want to learn from design to manufacturing and to discover all the possibilities. To build something is the motivation and the pretext for learning.

These profiles are usually people with free time, in a career pause or change. Let’s say that they (we) take it more as a hobby, but we are more motivated to create some knowledge or procedures.

And that’s quite contradictory, we are looking for the perfect quality, for us it is proof of a good job, and it shows that we learnt something rightly.

The other group are people with a clear goal. They need a product, frequently a prototype for a startup, and need it as soon as possible. They usually are interested in being in Motionlab because of the access to the machines.

It’s strange, a pity, but normal, more professionality means less time for the community and less time for sharing. I expected this startup profile to get more knowledge and learn from them, but it’s not easy. Anyway, what they do is impressive and an inspiration.

Version DE